Holly George

This week alone, I ordered stuff from China, searched the app of a certain giant retailer several times, happily opened a new package, and listened to a podcast about the growing difficulties of delivery workers. Mostly fun, but definitely not simple. Behind each of these actions exists a world of resources, employees, technologies, and logistical systems, all of which carry social and economic ramifications with them. It’s all indicative of the nature of trade and labor in the era of globalization and smart phones. Yet as a historian of the American West, I know that my online shopping anecdote is hardly news.

For at least 150 years, many western markets have opened to outside economic forces—be they mining interests or even theatrical circuits—and found the results to be at once enjoyable and frightening. Technological advancements (think: railroads) facilitated these changes and represented broader industrialization. That industrialization in turn convulsed labor practices and social life. This is precisely the story we tell in the fall 2019 issue of Utah Historical Quarterly.

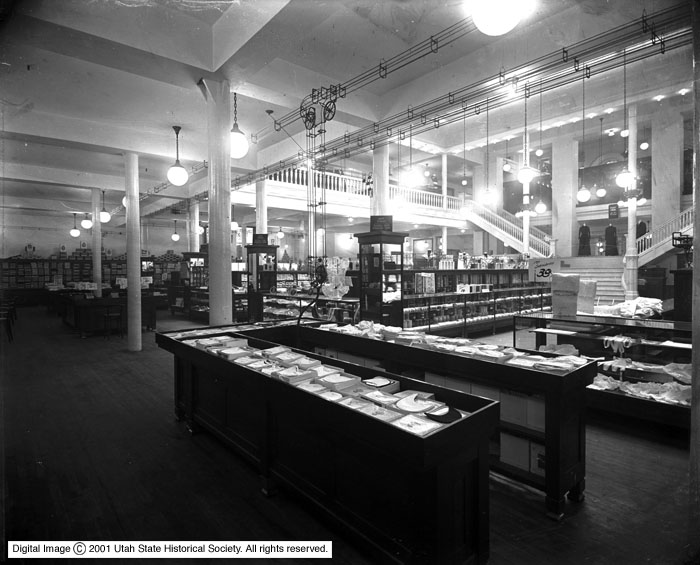

From statehood in 1896 to around 1910, Utah’s economy moved from one of villages and scattered mines to one based on mining, commercial farming, and smelting. As Leonard J. Arrington put it, once Utahns and others understood the possibilities of, say, copper mining, they focused capital and labor on the demands of eastern—rather than local—markets. This attracted money, immigrant labor, and machinery from outside the state and, “increasingly, the health of the economy came to depend on the continuance of favorable prices for the new staple exports.” Utah grew to have a specialized, largely extractive economy that was susceptible to the vagaries of external investors and markets.

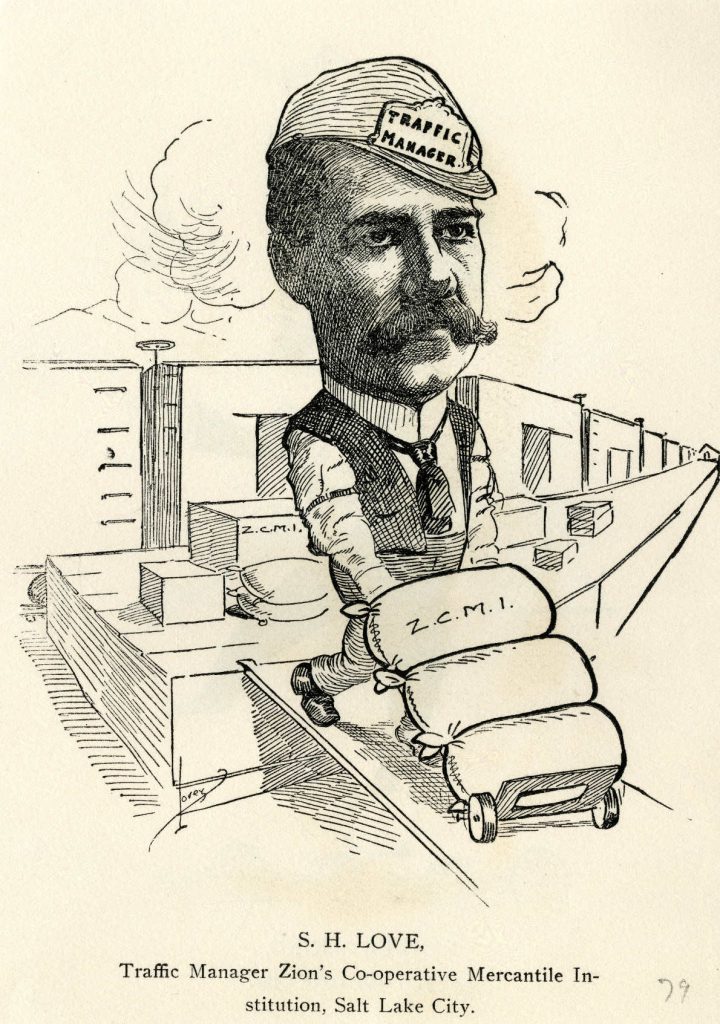

“No place needed rails more than Utah.” So writes Rod Decker as he analyzes the response of Utahns to the double-edged sword of railroad development. The arrival of the road greatly reduced the cost of coal and other items in Utah; on the other hand, the rail companies discriminated against Utah and other inland markets, charging more to ship shovels, coffee, or cotton goods from Chicago to Salt Lake City than on to San Francisco.

Utahns met the unfair rates with a range of responses that evolved over time. In the 1890s, a Republican-led state government sided with the railroads, hoping to stay in their good graces. In the early twentieth century, Democrats favored state regulation and eventually created a public utilities commission to keep freight rates low. All told, Decker argues, “railroads presented the first instance of an enduring Utah question: how to attract needed investment while preventing exploitation by big out-of-state corporations.”

The flipside of the environment described by Decker—a place of governors, railroad executives, and Commercial Club dinners—comes in the lives of other key players in Utah’s industrialization: immigrant laborers. In the fall UHQ, we examine their world through the lens of Bingham Canyon, Utah.

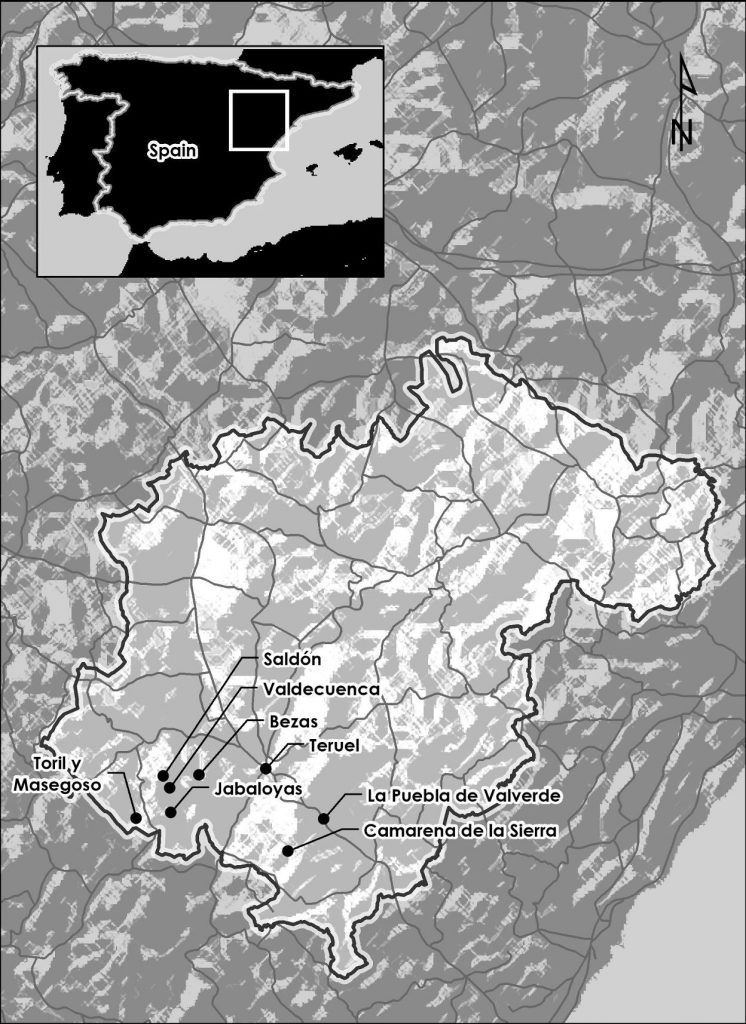

Beginning in the 1950s, Helen Zeese Papanikolas introduced a new chapter into the study of Utah’s past by paying attention to the waves of “new” immigrants who came largely from southern and eastern Europe and Asia to work in Utah. She shined an especially valuable light on her own people, the Greeks. In the latest UHQ, we reprint Papanikolas’s 1965 survey of immigrant life alongside the work of another path-breaking scholar, Raúl Ibáñez Hervás. Through painstaking research, Ibáñez has recreated the exodus of workers from the mountain villages of Spain to Bingham Canyon. Together, these pieces provide a glimpse of the mechanisms that enabled Utah’s industrialization and brought thousands of people from across the globe to power extractive industry in the West, as well as the world created by those immigrants.

So how does my online shopping habit affect real life, here in 2020? I’m going to let economists and journalists figure that out. In the meantime, we can see how a similar revolution in technology, industry, and labor played out in Utah a century ago.

Sources: Leonard J. Arrington and Thomas G. Alexander, A Dependent Commonwealth: Utah’s Economy from Statehood to the Great Depression (BYU, 1974), 7 (qtn); Charles S. Peterson and Brian Q. Cannon, The Awkward State of Utah: Coming of Age in the Nation, 1895–1945 (Utah, 2015), 80–81; Holly George, Show Town: Theater and Culture in the Pacific Northwest, 1890–1920 (Oklahoma, 2016).