By Cassie Clark, Ph.D., Public Historian

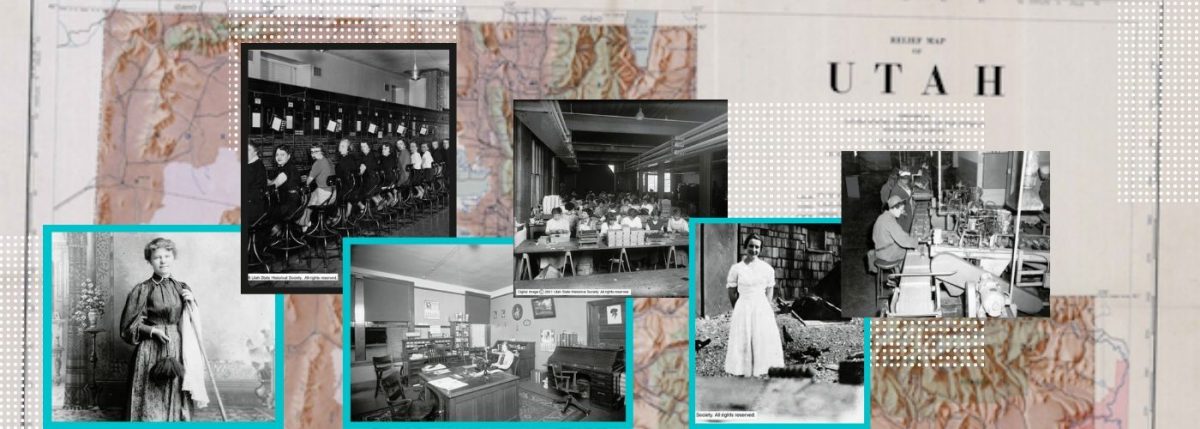

It is no surprise that the survival and growth of cultures are dependent on the efforts of all members of society. In Utah, women’s work has been essential in public and private life since the first Indigenous groups settled in the Great Basin. Women’s emotional and physical labor contributed to Utah’s political, economic, cultural, and religious identity. During Women’s History Month, join me to read more about some of the ways that women worked in Utah.

What Is Work?

Typically, we tend to define “work” as any task or labor completed in exchange for money. When we place a monetary value on work, we overlook all the tasks people perform that influence their communities. Labor is also valued based on who performs the work and what type of task a laborer completes. Work is also connected to a place someone does a job. People who “go to work” or work in public spaces are recognized more than labor performed “at home” or in the private sphere.

Women who work in the public sector are statistically underpaid and their labor undervalued or overlooked. For instance, work done in the home, including housework and child-rearing, is not valued as the work done by people who earn a paycheck. Work is much more than getting paid. People across the country and around the world regularly complete paid and unpaid tasks for themselves, family and friends, communities, and nations. When we broaden our definition of “work” to include any person who dedicates their emotional or physical labor to a task or moment, we recognize how women’s work influenced their homes, communities, and the nation. Throughout Utah’s past and present, women have worked in different places and performed many jobs.

Utah Women at Work

Historically, Native American women of the Shoshone, Goshute, Ute, Paiute, and Navajo tribes performed crucial jobs for themselves, their families, and their communities. For example, Northwestern Shoshone women worked by gathering seeds, roots, berries, wild honey, and bulbs. They also harvested potatoes, cactus, and wild garlic and made clothing.[1] Goshute women and girls gathered seeds, cooked, made clothing and pottery, and built shelters.[2] Ute women hauled wood, sewed and repaired clothing, took care of children, gathered food, and prepared and administered medicine for the ill.[3] European explorers and Euro-Americans enslaved Native American women and capitalized on their knowledge to colonize the land and conduct diplomacy.[4] Native American women’s work shaped their communities, cultures, and even how their people coped and adapted to difficult situations, including Indian Boarding Schools and forced removal to reservations. Of course, women’s work continued throughout the twentieth century up until today. For example, Native women have designed and created jewelry, clothing, and other goods that they sold in the United States’ ever-expanding market economy.[5]

People from other countries and across the United States began to move into what is now Utah during the 1800s. The first permanent immigrants were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (or LDS church), historically known as Mormons. When the first Mormons immigrated to Mexican territory in 1847, women set to work building a home and caring for and providing for their families and each other. They grew food, helped with construction projects, and traded and bartered goods.[6]

Immigrants from across the country and around the world continued to settle in Utah throughout the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. In addition to the first Mormon immigrants, people from China, Greece, Italy, Japan, and Hungry, to name just a few, settled in Utah. Women from each group found many ways to provide for themselves, their families, and their communities. They tended children and served and supported neighbors and friends. Women also earned money for goods and items they created. Some became teachers, seamstresses, and ran boarding houses and hotels. Others opened millinery and dress shops and worked in factories, laundries, or domestic servants. For instance, Fanny Brooks, a German immigrant of the Jewish faith, ran a millinery shop and bakery. She also ran a boarding house and later a department store named the Brooks Arcade. Brooks did all of this while raising six children and being an active Jewish community member. Brooks is only one of many dynamic women whose daily work influenced Utah for decades. Since immigrant groups settled in Utah, women worked hard to provide for their families and communities.

Utah’s industrial sector began to take root and expand during the late nineteenth century and continues to today. As more businesses opened and inventions made domestic labor more systematic, single and married women found work in Utah’s business sectors. Some women opened a business, became doctors and midwives, or outsourced work from their homes. The canning industry thrived because of women’s work. By 1914, Utah was fifth in the nation in food canning.[7] Women also worked in candy factories, for telephone companies, clothing factories, including ZCMI, and made soap, crackers, cigars, produced sugar, and performed many other jobs. Some women worked as editors, writers, and other parts of the newspaper and publication industry.[8] Many women were self-employed. For example, some women took sewing jobs that they completed in their homes. Of course, women did not limit their work to earning money. They continued to labor at home, serve their communities, and add their voice and advocacy in public and political spaces. Women who worked for wages and those who did not were equally influential to Utah’s evolving culture. Clearly, women’s work influenced all aspects of Utah life in pivotal ways.

Today, Utah women remain active in Utah’s political, economic, cultural, and religious landscapes. By expanding our understanding of the meaning of “work,” we can continue to uncover women’s voices and gain a more complete and expansive understanding of Utah’s complex history.

Join us each week during the month of March to learn more about how Utah women worked.

[1] Mae Timbimboo Parry, “The Northwestern Shoshone,” in A History of Utah’s American Indians, Forest Cuch, Ed (Salt Lake City: Utah State Division of Indian Affairs/Utah State Division of History, 2003), 28, 30.

[2] Dennis R. Defa, “The Goshute Indians of Utah” in A History of Utah’s American Indians, 78.

[3] The Northern Utes, 169.

[4] Forest Cuch, Ed., A History of Utah’s American Indians, 87-88, 126, 129, 280. Sherry Farrell Racette, “Nimble Fingers and Strong Backs: First Nations and Métis Women in Fur Trade and Rural Economies,” in Indigenous Women and Work: From Labor to Activism, Carol Williams, Ed. (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 149. Juliana Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 1-2.

[5] Dennis R. Defa, “The Goshutes Indians of Utah,” in A History of Utah’s American Indians, 118. Gary Tom and Ronald Holt, “The Paiute Tribe of Utah,” A History of Utah’s American Indians, 163.

[6] Miriam B. Murphy, “Gainfully Employed Women: 1896-1950,” in Women in Utah History: Paradigm or Paradox?, Patricia Lyn Scott, Linda Thatcher, Eds. (University of Colorado Press, 2005), 185.

[7] Carolyn Bulter-Palmer, “Building Autonomy: A History of the Fifteenth Ward Hall of the Mormon Women’s Relief Society” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 20, 1 (2013): 69-70.

[8] Miriam B. Murphy, “Gainfully Employed Women,” in Women in Utah History: Paradigm or Paradox?, 187-193.