By Christine Cooper-Rompato

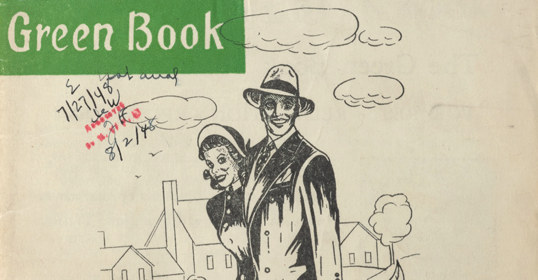

My forthcoming article in Utah Historical Quarterly, “Utah in the Green Book,” explores the history of hotels where African Americans could spend the night in Utah during the period of segregation. Many hotels across the U.S. were “white only” until the 1960s, and in 1936, Victor Hugo Green, an African American mail carrier living in New York City, wrote and published the Green Book. It was a travel guide featuring businesses in New York and then across the U.S. that catered to African Americans. Green revised his guide yearly until his death in 1960, at which time his wife, Alma, took over the publishing until its final edition of 1966. With the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the segregation of housing and restaurants was declared illegal, and the last editions of the Green Book included a list of those states with additional anti-segregation laws. Over the decades, the Greens had also expanded the guide to become multinational, including accommodations in Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean. Most of the editions can be found online through the New York Public Library; a slideshow is also available through the Smithsonian.

My idea behind researching this article was to use Green’s travel guide as a launching point to explore the experiences of African American tourists, visitors, hoteliers, and restaurant owners in Utah, based on the available records including newspapers and oral histories. In researching the hotels, I found that the tax records (housed in the Salt Lake County Archives) were especially helpful. As a white medievalist who works in an English Department, I had a lot of reading and researching to do to try and understand both what the experience of segregation was like for African Americans in Utah, and how to use more modern records to construct a history of the hotels, patrons, and proprietors.

The stories of the hotel owners could be very difficult to read because of the contemporary representations of racist hatred and violence. James and Ida Hampton owned the J. H. Hotel at 250 West South Temple, which was the first Utah location listed in the Green Book, in the 1940 edition. The hotel was advertised in newspapers as “The newest and best hotel West of Chicago and East of Los Angeles,” with rates starting at fifty cents a night. After James died in 1946 his wife took over the hotel. In 1948, Mrs. Hampton was the victim of a brutal, racially motivated attack, in which several juveniles, led by two white men, completely destroyed a new home she was building and defaced the remains with racist graffiti. The two adults received barely a slap on the wrist and were released on parole. Conversely, in the late 1940s, the J. H. Hotel became the target of vice raids, with the police eventually shutting the establishment down in 1950. Ida Hampton died within two years after the hotel was closed, never having rebuilt her home that had been destroyed.

On a more positive note, hotel ownership could also be a route for African American women to become successful business owners and influential community leaders, as the experience of Leager V. Davis, owner of the Royal Hotel at 2522 Wall Street in Ogden, demonstrates. Her hotel became a gathering place for social and political meetings, including the Ogden chapter of the NAACP. Unfortunately, Davis’s hotel, too, was the target of police raids, and her husband the victim of violence.

I encountered several challenges as I worked on this essay, and these challenges are future projects that need to be explored. National parks appeared in the Green Book for the first time in the 1950s, and the Utah listings included Zion and Bryce. But were the Utah parks (and western parks in general) segregated or desegregated before the 1950s? Studies on national parks in the east demonstrate that discriminatory practices were entrenched in the park system; a recent film by Ken Burns addresses segregation in Hot Springs, Shenandoah, and Great Smokey Mountains national parks, as well as the George Washington Birthplace National Monument. However, I have located nothing that either proves or disproves the practice of racial discrimination in Utah’s national parks. Discussions with park rangers and archivists at Bryce and Zion pointed me in some helpful directions, and it is in these directions that I will be turning this year. The archivist suggested I look at the company that controlled travel to and accommodations within the parks, the Utah Parks Company, a subsidiary of Union Pacific Railroad. Zion’s archivist also suggested I could look in the history of the other camping sites located around Zion, which I plan to do.

Several questions will drive my research of whether segregation occurred at Utah’s national parks. First, I would like to discover if and where African Americans and other people of color were employed at the parks from their creation through the 1960s. I hope a trip to visit the Zion and Bryce archives can help me answer this question. I also assume the Utah Parks Company employed non-white employees on the trains and in their services in parks, which I plan to follow up with the Union Pacific archives. In addition, I have spent a fair bit of time looking at records of the Civilian Conservation Corps, which formed in the 1930s and employed young men on public works projects across the U.S. Several companies worked in southern Utah building trails, roads, and monuments, and although racially integrated corps existed in Utah, I haven’t found evidence yet that those corps were working in Bryce or Zion.

Second, I would like to explore how popular Utah’s national parks were with African Americans and other people of color. Much advertising of the parks presented the view that all visitors were white, but this, of course, is not an accurate representation of park visitors. I have searched through the African American Newspapers, 1827–1998 database for anecdotal evidence of men and women traveling to the national parks and have collected over a hundred such social announcements: newly married couples vacationing to parks, sisters traveling to California and stopping at parks on their way, and so forth. Based on these announcements, the two most popular parks seem to be Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, which has led me to consider including them in the study as well. (The Utah Parks Company provided services to the Grand Canyon). Yellowstone appears to have been the most widely advertised of the parks; African Methodist Episcopal churches in the East sponsored presentations on its wonders, and African American newspapers advertised round trips from eastern cities to Yellowstone.

Third, and the most difficult to uncover, are accounts of African American experiences that attest to the role of discrimination at Utah parks. When I began this project, a historian of leisure in the twentieth century advised me, “Just assume that there is segregation. But it can be hard to locate documents that describe it, because so much is unstated.” I have read a number of oral interviews (such as those included in the University of Utah’s “Interviews with African Americans in Utah” project) to see if any interviewees mention their experiences in parks. I’ve looked at published memoirs as well and have located just a few anecdotal accounts, including one that I close the “Utah in the Green Book” essay with: a recent memoir by Lauret Savoy, a professor at Mount Holyoke College, describes how as a young girl traveling in national parks in California in the 1960s, she had tried to buy a postcard but the cashier treated her very poorly. In contrast, in a newspaper article from 1959, an African American travel writer describes how he and a group of African American men traveling through the West were well received at the Rocky Mountain National Park and invited home by a white employee.

Even with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (and the subsequent Fair Housing Act in 1968), several interviewees who took part in the “Interviews with African Americans in Utah” project attested to the ongoing discrimination that they faced in Utah. Just a few days ago I read an article on CNN.com that describes racial covenants in housing contracts: although these racial clauses, which seek to exclude non-white residents, were originally created during the time of segregation, many housing contracts today still include them in the fine print. The overall assessment from the historian Kirsten Delegard, founder of the “Mapping Prejudice Project” in Minneapolis, is shocking: “Pretty much every community in the country is going to have racial covenants” in their housing documents, she explains.

More work needs to be done to uncover this history of discrimination, and locating racial covenants in contemporary contracts is one such avenue of research. Many Utahns will no doubt be horrified to learn that in 1939, a white realtor proposed creating a “special residential district” (i.e., a ghetto) for African Americans so as to prohibit people of color from purchasing houses or renting throughout the city. The November 2, 1939, Salt Lake Telegram describes the realtor’s racist rhetoric, as well as protests against the plan. This took place just a few months before the J. H. Hotel became the first listing in the Green Book and gives a wider perspective of the level of racial discrimination in Salt Lake City before desegregation.

Christine Cooper-Rompato is an Associate Professor of English at Utah State University, where she teaches medieval literature.