By David Rich Lewis

Olivia Coombs was dead. George Wood shot her and her daughter, Emily, on July 28, 1862, in Cedar City, Utah Territory, and then beat them with the butt of his pistol. Woods was tried, pled guilty, and was sentenced to life in prison, only to be pardoned three years later. That much is clear, but beyond that the story of Olivia’s murder meanders between forgetting and remembering. The historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich picks up the threads of Olivia’s killing and explores the “why” of it in her article, “Juanita Brooks’s Footnote,” published in the Utah Historical Quarterly (Summer 2022). Ulrich’s essay is a master class in historical research, the way a historian serves as detective, interpreter, and sometimes participant in creating and revising our understanding of the past.

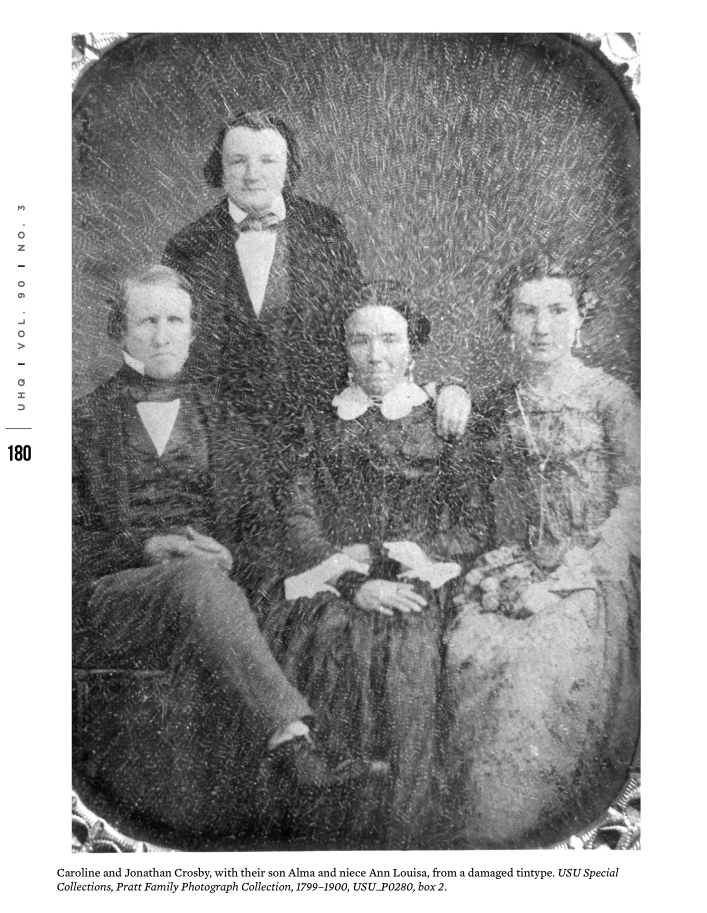

Ulrich came across Olivia Coombs’s story through a footnote in the historian Juanita Brooks’s iconic book, The Mountain Meadows Massacre (Stanford University Press, 1950). In that note, Brooks recounted a family story told to her by Olive B. Millburn in the late 1940s about her grandmother’s death, indicating that Olivia—cast as a beloved teacher—had been murdered because she was too curious about the culpability of Cedar City residents in the 1857 massacre. But Ulrich had stumbled across Olivia before in the diaries of Caroline Barnes Crosby in a very different context that portrayed a more problematic person. So Ulrich set out to reconstruct Olivia’s world to understand the intergenerational family narrative presented in this footnote.

The story Ulrich uncovers is wildly complex, requiring a board full of photos and connecting strings and post-it notes, like a modern TV detective show. Ulrich mines genealogical, legal, and primary documents in search of Olivia and then weaves together each piece—sometimes contradictory, often incomplete—in the context of what we know about nineteenth-century American society, Utah and Latter-day Saint culture, and the roles and complex experiences of women. Like others, Olivia lived in an unstable world. She was a Mormon convert, had four daughters and two sons, lived in this patriarchal system with multiple men over the years, and experienced the disorientation of no-fault Mormon divorces and unstable homes. She moved from California to Utah, but her situation deteriorated. She struggled financially, psychologically, theologically. Through Coombs’s messy life experience, Ulrich reminds us that “Saints” was an aspirational title as much—or more than—it was a lived community experience. In the end she posits that the family memory about Olivia’s murder captured in that footnote was unlikely, that it passed from a granddaughter wanting to rehabilitate Olivia’s memory to a historian also searching for her place in Mormon Utah culture as she worked to uncover the messy truth about Mountain Meadows. The story served the purposes of both granddaughter and historian in that moment. As Ulrich reminds us, “History is always a dialogue between present and past, between the assumptions and experiences historians bring to their projects and the documents they are able to discover” (p. 183).

It is wonderful to see the work of a Pulitzer Prize–winning professor emerita from Harvard University turn up in the UHQ. It reaffirms the value and scholarly quality of our journal, and it adds another elegant layer to that ongoing project we call Utah history. Yet, in celebrating Ulrich’s essay, I want to tell you a different but equally important story. This is about a 21-year-old university student writing his senior thesis. With the encouragement and guidance of his professors and the editorial work of Stan Layton, he published his first piece of scholarship in UHQ. It was not a master class in historical interpretation, not a prize-winner, but it was a start that launched an academic career that continues to grow, now going on 44 years. That student author was ME. But perhaps, if you think about it, that was also YOU and the story of your start in Utah history.

What makes the Utah Historical Quarterly such a valuable journal is that for 90 years it has provided a place for ALL of us—whether K-12 or university student, history enthusiast or honored professor—to learn and practice our art, to look for new voices and sources, to tell (and to read) new and inclusive stories, and to reinterpret our diverse past in ways that connect past to present and ourselves to each other. UHQ is a peer-reviewed and carefully edited source of reliable historical information, the scholarly foundation for books, articles, lectures, student papers, news stories, and social media posts. It is an enduring asset and resource for future generations. It is (and always has been) the right place for telling important regional stories and developing our next cohort of Utah historians.

And that’s the “why” of my blog post—why it’s important to support the mission and vision of the Utah Historical Quarterly, the Utah State Historical Society, and the Division of State History. Your membership underwrites the costs of production, printing, and distribution of UHQ, as well as other products and programming, including public events and online publications like History to Go and I Love Utah History. You make the UHQ possible through both your scholarly work and financial support—it wouldn’t happen without you. Please, become a member today or renew your membership, encourage a colleague to join, or maybe step up to become a sponsoring member. This year, USHS is expanding both print and digital subscription options for current UHQ content, so you can choose how you want your journal delivered. Visit the UHQ webpage for a full list of membership options.

Now, more than ever, it’s important to support a quality Utah Historical Quarterly, a journal that makes room for everyone, from Pulitzer Prize–winning historians to the student authors who are our future.

David Rich Lewis is an emeritus professor of history at Utah State University and the former editor of the Western Historical Quarterly. He has served on the Utah Board of State History since 2015.