by Katie Barber

Katie excelled during her internship with State History, so we hired her for the summer.

How often do you think about where you are in the world? This isn’t some great metaphysical question. I am referring to your present physical location, your exact geographic place on Earth, the latitude and longitude of your presence. Do you consider the latitudes and longitudes traversed on your commute, the amount of distance traveled toward or away from the Greenwich meridian with every single move you make? I certainly do not, but I would say I am a fan of maps—ways one might contextualize their place in the world. Maps transmit an organized sense of place, an undeniable evidence that proves someone has been in that place before you. Maps have been drawn with the stars and etched into rock the entire duration of recorded history, using standards of steadfast landforms and waterways. We have used these standards to navigate, define cultural boundaries, establish bodies of government, and measure people and geography alike.

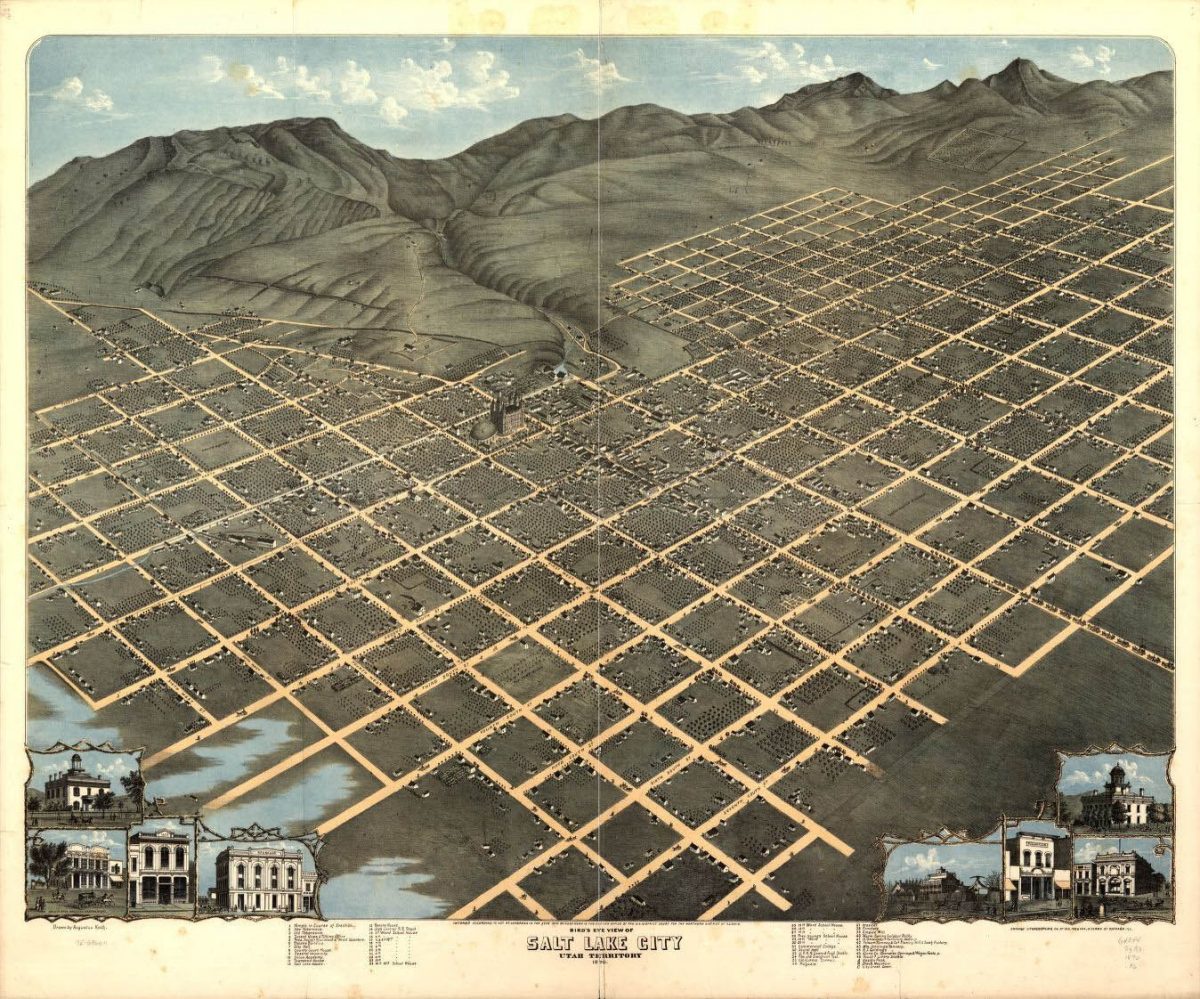

Spend enough time at the Utah Division of State History, located at 40°45’46.1″N, 111°54’15.3″W, and you might see a few maps floating around. It comes with the territory (pun intended) for a division formed by expert librarians, GIS analysts, archaeologists, historians, and preservationists who are working to preserve and share the history of a state comprised by about 84,900 square miles. It was here that I learned—despite being a map fan® and lifetime Salt Lake resident fully aware of its city-planning-textbook-example status—that Salt Lake City possesses its very own meridian.

Established in 1855 in downtown Salt Lake City at the intersection of what is now South Temple and Main Street, the Salt Lake principal meridian is a literal guideline used for surveying throughout Utah. 100 miles to the east lies a second guideline used for surveying in Uintah County, the Uintah principal meridian, which was established in 1875. Each principal meridian is also accompanied by an east-west baseline, marking the reference latitude. These guidelines are part of the Public Land Survey System (PLSS), which divides land in 30 states into townships that are 6 square miles. Townships are further divided into 36 square one-mile sections. Reference markers detailing a location’s proximity to the principal meridian outline these survey sections and were originally constructed by piles of rock or wooden stakes. Today’s markers are usually made of concrete or iron.

The changing technology of plotting these points through efforts such as the PLSS is reflected in how most individuals interact with maps contemporarily; even if you are not a surveyor, you rely upon these techniques on a daily basis. It is now easier than ever to get from point A to B with a couple swipes on a smartphone, which you might then use to geotag a social media post. The continued integrality of navigation with our technologies, old and new, is surely a testament to some sort of innate need to say “I was here.”

Maps are a record of where we have been, but they also help us decide where we want to go. It is a common trope exemplified in the “Congratulations” and “Good Luck” sections of the greeting cards: the “roadmap of life,” “setting the course,” “keep your eye on the horizon,” or “carve your own path.” We have always used the idea of navigation to mark time and set goals for the future. And it’s a theme particularly associated with the western United States, as its historical identity is combined with the ideas of exploration and discovery. The desirable “Frontier” typically conjures up sepia-toned images of a vast expanse, and allusions to such romanticism endure today in countless forms, found everywhere from tourism campaign signs to indie band lyrics.

While such expressions of place seem to be pointed exclusively towards the future, a look beyond billboards and between the lines of lyrics reveals they are actually rooted in the past, for every allusion to geography is synonymous with history. The mediums through which we consider the question “where are we in the world” may have changed over time—we may not solely interpret the night sky to get our bearings or refer to rock pile markers in organizing land—but we still continue to ask the question whether we realize it or not, attempting to find an answer in grids on a survey or pixels on a screen. When we ask this question, we are tracing the movement of people through time and space—those who have already said “I was here.”

Take a look at how UDSH is tracing history through maps here. You may just gain a better sense of where you are in the world for it.

As you can tell, Katie is a creative writer. She recently graduated with a B.S. in Health Society & Policy and a B.S. in Communications (focusing on science, health, risk and environment). If you are interested in learning more about Katie, please contact Kevin, her supervisor, at kfayles@utah.gov.

“Bird’s eye view of Salt Lake City, Utah Territory 1870.” Courtesy Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, G4344.S3A3 1870 .K6