By Laurie J. Bryant, Independent Historian

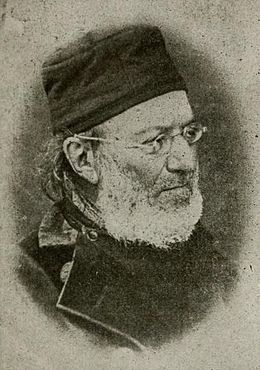

[On July 2nd, at the Salt Lake City Cemetery, we unveiled a monument for 55 individuals who died at the “insane asylum” in the 1870s and 1880s. We asked the researcher, Laurie J. Bryant, to tell us more about one of the individuals.]Louis A. Bertrand (1802-1875) was born Jean Francois Flandin in southeastern France, near the port city of Marseilles. He had an excellent conventional education and then became a world traveler. On his return to France, he joined in the Revolution of 1848 as a socialist. Disappointed by the result of the Revolution and the coronation of Emperor Louis Philippe III, he was jailed for three months in 1848 because of his opposition and probably changed his name about that time.

The first LDS missionaries – John Taylor and Curtis Bolton – arrived in France in 1850. Bertrand met with them in Paris and soon became a convert. His wife, however, did not. Bertrand, by that time a high priest in the church, went with other LDS missionaries to the Channel Islands where he produced most of the first French translation of the Book of Mormon.

His travels continued. Leaving his family in France, Bertrand sailed for the United States in 1855, continuing on to Utah with the Charles Harper wagon company. Impoverished, he lived in one of Brigham Young’s homes, but returned to France late in 1859. After four more years of work as the church’s mission president in Paris, he returned to Utah in 1863, discouraged by his failure to gain approval to preach in his own country. Again, he left without his wife and never saw her or his sons again.

In Utah, he joined Brigham Young in championing the silk industry. The 1870 census found him in Tooele, a farmer living with a farm family. He devoted himself to caring for a silk plantation, and never remarried. Bertrand also wrote regularly to the Deseret News, offering sharp criticisms of the methods of local grape-growers, advice on growing mulberry trees, and critiques of olive oil, as well as his political views. He was an admirer of Prince Bismarck, and of all things French.

Late in 1873, the tone of his letters became increasingly anxious, addressing European politics, cigarette smoking, the Pope’s wealth, and a new invention – unbreakable glass.

Anguish over his family, and possibly an inheritance denied because he could only have received it under his real name, eventually led to a serious emotional breakdown. The Deseret News reported on March 11, 1875, that “his reason began to give way” and he was taken to the City Hall, almost certainly because he could be restrained in the city jail that was in the building. He was taken to the Salt Lake City Insane Asylum near 1300 South and Wasatch Blvd. when his condition worsened, but even as sanity began to return, he became physically ill and died on March 21, 1875. He is buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave at the Salt Lake City Cemetery, near the eastern end of Plat E. For a man described in the Salt Lake Herald as “esteemed by all who knew him, and especially by those who appreciated his scholarship and literary abilities,” this hardly seems appropriate.

Laurie J. Bryant

7/3/2019

(Most of this information comes from: Richard D. McClelland, “Not Your Average French Communist Mormon: A Short History of Louis A. Bertrand.” Mormon Historical Studies, 2000. The author calls the Asylum “the sanitarium,” which puts a nice gloss on it.