By Amy Barry, Utah Cemetery & Burials Program Manager

Marking burials with gravestones has always had a myriad of meanings. The more modern connotation has reflected European traditions ingrained in America’s immigrants. It wasn’t until the 19th century that gravestones did more than reflect the final resting place of someone. Inscriptions began to appear that included name, date of birth, date of death and perhaps a few words or a phrase to honor the deceased. As this tradition crossed the pond and took hold, it became a widespread practice for all classes. Designs have become more extravagant, artistic, and personalized.

The tradition of honoring our dead naturally extended to those who died in military battles. On September 11, 1861 the War Department issued orders that directed the Army’s Quartermaster General of each military post to bury officers and enlisted soldiers in their cemetery and keep a register of all burials. This order directed a wooden headboard be placed at the head of each grave. These headboards were painted white and all information was painted black. Only Union soldiers and officers were covered under this general order.

Wooden headboards didn’t last long in the elements and needed to be regularly replaced. When burials exceeded 100,000 and projections showed the final number of Civil War casualties could be somewhere near 300,000, Congress realized maintaining wooden headboards was financially unfeasible. Following much debate, in 1873 Secretary of War William Belknap instituted the first design for Union soldiers. The wooden headboard replacement for military gravestones was a slab of marble with a sunken shield as the design with a number, name, company, regiment and state inscribed for identification.

This original design became known as the “Civil War” type and was available to the Union Army in national cemeteries only. In 1879, Congress authorized the stones to be available for Union Army veterans in private cemeteries as well. This sunken shield became the design for eligible unmarked graves of soldiers from the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Mexican and Indian Wars. At the end of the Spanish-American War it was determined to allow that same design, but with an additional inscription of “SP-AM” War to distinguish those veterans. To ensure uniformity, Congress first authorized the use of the shield design for unmarked graves of unknown soldiers and extended the authorization to civilians in post cemeteries in 1904.

Congress allowed headstones to be furnished to Confederate soldiers starting in 1906. However, the design varied in a more pointed top and there was no shield. It wasn’t until 1930 that the War Department authorized the inscription of the Confederate Cross of honor in a small circle to be placed above the standard inscription of name.

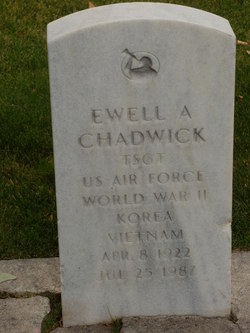

Following WWI, a new design was approved for all veteran graves except those of the Civil and Spanish-American Wars. The current design is now known as the “general” type, featured the inscription of name, rank, regiment, division, date of death, and state from which the veteran came. In addition, the use of a religious emblem was adopted for government-issued headstones. In the beginning, only the Latin Cross and the Star of David was allowed. Over the years additional emblems have been approved and now number 79 options.

Simple inscription Latin Cross Emblem

Additional inscriptions

Addition of spouse at bottom

Spouse inscription of the back side along with grave location

Modern inscription including Mormon Emblem

Over the years many more changes were allowed with inscriptions, additions of specific wars, material and style. The most notable change was in 1936 when flat markers were approved due to the rising number of military veterans in private cemeteries that only allow flat markers.

Fort Douglas Cemetery

While Civil War-era headstones are not prominent in Utah cemeteries, you will find sections in Fort Douglas Cemetery and Mount Olivet Cemetery in Salt Lake City. The Civil War-era burials in Fort Douglas represent soldiers from the 3rd California Volunteer Infantry tasked with protecting the Overland Mail Route during the time federal troops had been recalled to fight in the Union Army of the Civil War. Most of these soldiers died in the Bear River Massacre.

In 1864 soldiers at the post began work to improve the cemetery and erected a monument to the memory of those men killed at Bear River and Spanish Fork.

In the Fort Douglas Cemetery you will find an array of military gravestone design (minus the Confederate southern cross). There are notable people buried in the cemetery and a memorial to WWI German & Italian POW’s and WWII POWs who were German, Italian and one Japanese (includes the nine German POWs murdered at Camp Salina on July 8, 1945 by a camp guard).

While burials are still occurring in the cemetery, the last plot was reserved in the 1970s. There are currently over 1,300 people interred in the cemetery, ranging from soldiers who died in battle, veterans and their families, POWs, civilians, and a monument to a beloved horse buried outside the fence.

Fort Douglas is hosting their Annual Fort Douglas Cemetery Tour on October 26, 2019 from 1:00 – 4:00 P.M. Kids and adults can learn more about Utah’s military history. There will be re-enactors stationed across the cemetery to bring to life stories of people buried there and a Gravestone Designs Through Time tour, which is hosted by Fort Douglas Military Museum, Utah State History, the African American historical and Genealogical Society, and Utah State Archives.