Douglas H. Page Jr., et al., “Charcoal and Its Role in Utah Mining History,” Utah Historical Quarterly 83 (Winter 2015): 20-37

The winter 2015 UHQ introduces readers to the dozens of charcoal kilns, now abandoned, that dot the Utah landscape. These kilns are visible reminders of a once profitable and ubiquitous industry. They are also a remarkable visual display, revealing the kiln’s unique and varied designs and the often remarkable craftsmanship that went into their construction. We thank Doug Page, a retired forester, for providing the text and photos.

Text and Photos by Douglas H. Page Jr.

While charcoal production technology is estimated to be anywhere from 6,000 to 8,000 years old, charcoal produced in “beehive” shaped kilns is a nineteenth-century invention. The parabolic dome design was introduced in 1868 by James C. Cameron in Michigan and quickly became the industry standard. Most Utah kiln sets are of the parabolic dome design. A few sets are the more simple conical design. Both designs are often referred to as “beehive” kilns.

The earliest record of charcoal kiln construction in Utah is at Rush Lake in Tooele County in 1869, while the latest construction of a kiln set in Utah—in Carbon County’s Spring Glen—dates to 1890. Many charcoal kilns continued to produce charcoal into the early twentieth century until the use of charcoal was replaced with coal. Here former forester Doug Page provides photos and captions of kiln sites around the state (and one in Wyoming).

Towards the end photos by George Edward Anderson (1860-1928) of charcoal kilns dated ca. 1890s.

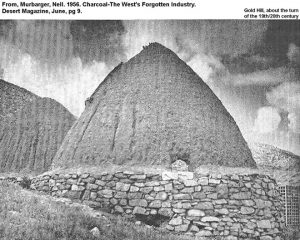

Gold Hill

- On the north end of the Deep Creek Mountains at Gold Hill were once two charcoal kilns with stone bases and ceramic tops. These kilns were unique to Utah due to the ceramic construction material. Only a few kilns anywhere in the United States were constructed using ceramic materials. Few specifics are known about these, except that they were in operation in the 1890s, presumably producing charcoal for the smelter at Gold Hill. This photo, taken by Nell Murbarger and published in her article “Charcoal: The West’s Forgotten Industry” in the June 1956 edition of Desert Magazine, shows the tops still largely intact. Today only one kiln has any ceramic remaining and most of the stone bases of both kilns are gone. Wood harvested for these kilns would have been pinyon pine and juniper.

- The Gold Hill kilns are located on State Trust Land several hundred feet northwest of the main intersection in the town of Gold Hill. This photo was taken in September 2013 and shows a close-up of the interior of the more intact kiln. The ceramic top and the stone base can be seen. There is also a small lime kiln on the site just downhill (north) of the charcoal kilns.

American Fork Canyon

Three kilns were constructed on a small piece of private land at Three Kilns Spring 8.3 miles northeast of Frisco. Charcoal from this site went primarily to the Frisco smelter. The kilns are located on the eastern edge of the pinyon-juniper woodland, thus wood harvest activities would have been primarily to the north, west, and south of the site. The County Line site, with four kilns, is located 2.25 miles to the west-northwest, and the Sawmill North (Seven Kilns) site is located three miles to the southwest. It is likely that pit kiln sites may be found in between these sites. Photo was taken in September 2011.

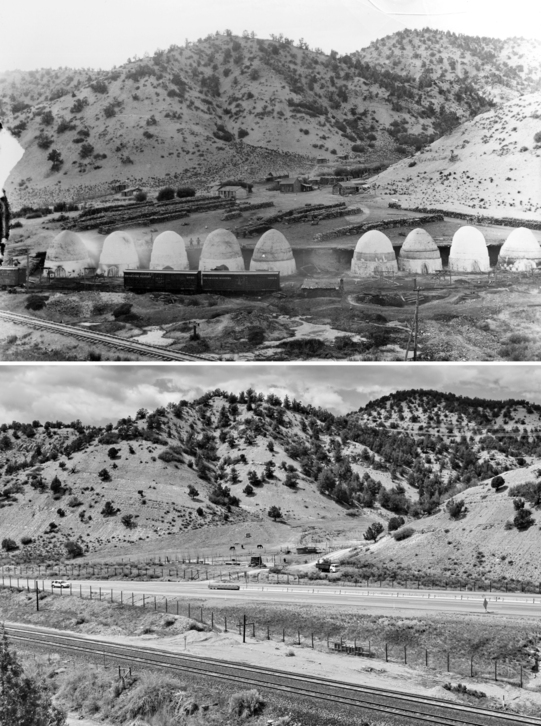

Spanish Fork Canyon

This paired photo set shows the location of the McCoy and McAllister (M&M) charcoal kilns (Spanish Fork Canyon) in about 1890 (top) and in 2013 (bottom). No evidence remains today of the ten kilns that once occupied this site. A four-lane highway now runs where the kilns once sat. The 1890 photo has some wonderful detail. Workers can be seen in various locations around the nine standing kilns and the one collapsed kiln. The kiln doors are all sealed with props holding the doors shut. What appears to be a bucket of whitewash sits on the rear loading ramp between kilns four and five (counting from the left). Whitewash was used to seal small cracks in the kilns before firing, thus allowing better control of the burn rate. These kilns appear to have had the exterior whitewashed, where at other sites around the state, the interiors were treated. Behind the stacks of wood are the outlines of men working at the site. Photo credits: ca. 1890 by George Edward Anderson; 2013 by Douglas H. Page Jr.

Piedmont, Wyoming

Piedmont, Wyoming, was the site of five charcoal kilns built in 1869 and operated until the early twentieth century. The Piedmont site is now maintained and interpreted by Wyoming State Parks and Cultural Resources. The kilns produced charcoal for Salt Lake City smelters from wood harvested from Utah’s Uinta Mountains. Wood harvested for the kilns would have been lodgepole pine, aspen, spruce, and fir. Wood was delivered to the kilns via sled in winter and, undoubtedly, via rail from Hilliard some 11.5 miles southwest of Piedmont. The thirty-six-mile long Hilliard Flume delivered wood from the mountains for railroad ties and for charcoal production to twenty-nine kilns at Hilliard. It is located in Piedmont—now a ghost town—along the original line of the Union Pacific Railroad (now County Road 173), eighteen miles east-southeast of Evanston (twenty-six driving miles). Piedmont is famous for delaying the train carrying Thomas Durant (vice president of the Union Pacific) to the Golden Spike ceremony until workers received their back-pay from the railroad. The ceremony was scheduled for May 7, 1869, but took place on May 10, 1869, due to the delay. Photo taken April 2013.

Frisco

The photos that follow are of a number of kiln sets that all supplied charcoal to the Frisco Smelter. We know of eleven sets of kilns (with forty-one kilns) associated with the smelter. There were many more pit kiln sites, but the location is known for only some. The eleven kiln sets are scattered throughout the San Francisco Mountains, primarily on the east side, with two sites located on the east side of the Wah Wah Mountains. Development of the Frisco charcoal industry began in 1877 shortly after discovery of silver at Frisco, and operations continued until 1885, ending after the Horn Silver Mine collapsed and the smelter closed. Each set of kilns was independently owned and operated, with the exception of the five kilns at Frisco that were owned and operated by the mining company.

Kiln sets were spaced far enough apart so that conflicts between operators were minimized. Wood harvest was typically done within an irregular one-mile radius of the kiln site, depending on topography, accessibility, and availability. Wood harvested for the Frisco Smelter was pinyon pine and juniper. Some ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir were also harvested from the local area, used primarily for buildings and structural material.

- Carbonate Gulch Kilns, viewed from the north-northeast, February 2014. Built primarily to supply charcoal for the smelter at Frisco (2.1 miles to the south-southwest), two pairs of kilns can be found on BLM land in Carbonate Gulch. The larger pair can be clearly seen in the sagebrush opening; the smaller pair are somewhat hidden some 260 feet to the right (northwest) of the larger and against a small hill in a side drainage. Kilns were often built against hillsides to facilitate loading through the upper doorway, avoiding the need for large ramps. On this site, cutting went one mile west but only 0.1 miles to the east. Slope and unavailability of suitable wood limited the eastern wood harvest and transport. Old harvest roads can still be found in the area.

- Carbonate Gulch Kilns, July 2013. Close-up of the front doorway of one of the larger pair. The kilns were built primarily out of native stone and the doorways of the larger pair were lined with brick. The smoother surface of the brick would have made it easier to seal the door during combustion.

- The Carbonate West site is in the head of a small un-named drainage 1.4 miles southeast of the Carbonate Gulch kilns and 1.2 miles northeast of the Frisco kilns. Charcoal from this site would have gone to the Frisco smelter. The site contains the foundations of two kilns, an unidentified straight stone wall/trench with creosote char, and three pit kiln sites. This photo shows one of the pit kiln sites in July 2013. Pit kilns are sometimes associated with constructed charcoal kilns. While they did not produce as high a quality of charcoal, they could be constructed quickly, which may have allowed for the kiln operators to rapidly respond to increased demand for charcoal. The Carbonate West site is not mapped on current USGS topographic maps, unlike most Frisco kiln locations that are.

- Copper Gulch contains two sets of kilns that were part of the Frisco kilns, supplying charcoal to the smelter at Frisco. Both are on privately owned land behind a locked gate. These are the only known kiln sets on the west slopes of the San Francisco Mountains. This August 2013 photo is of the interior of the one intact kiln and shows the whitewash coating that was being applied over the creosote residue prior to the next burn. That burn never occurred. What appears to be a shadow on the top is not: it is where whitewash had not been applied. Whitewash had been applied below five feet but not yet applied above that. Whitewash coating was used to seal small cracks in the walls so that the rate of burn could be controlled. The Copper Gulch kilns are 2.6 miles northwest of Frisco and 2.1 miles west of Carbonate Gulch. Unlike most Frisco kiln locations that are identified on current USGS topographic maps, the kilns in Copper Gulch are not mapped.

- Three kilns were constructed on a small piece of private land at Three Kilns Spring 8.3 miles northeast of Frisco. Charcoal from this site went primarily to the Frisco smelter. The kilns are located on the eastern edge of the pinyon-juniper woodland, thus wood harvest activities would have been primarily to the north, west, and south of the site. The County Line site, with four kilns, is located 2.25 miles to the west-northwest, and the Sawmill North (Seven Kilns) site is located three miles to the southwest. It is likely that pit kiln sites may be found in between these sites. Photo was taken in September 2011.

- Close-up of one of the kilns at Three Kilns Spring showing both the front and rear doorways. These kilns were built of native stone. After the charcoal production era, one of the kilns was used as a line-shack for livestock and was fitted with a wooden roof and wooden door. Photo was taken in September 2011.

- Kiln Spring site is located on a small parcel of private land in the Wah Wah Mountains, 14.5 miles southwest of Frisco and 6.5 miles north-northeast of the Lamerdorf Canyon site. There were five, small conical-shaped kilns built at Kiln Spring. The kilns here were generally smaller and the construction method was not as refined as at other Frisco kiln sets where Cameron’s parabolic dome design was used. Charcoal went to the Frisco smelter. The San Francisco Mountains (location of nine of the eleven Frisco kiln sets) can be seen in the background. Photo taken April 2012.

Near Price

Several old photos by George Edward Anderson (1860-1928) of charcoal kilns dating ca. 1890s can be found in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections in the BYU digital library (http://tinyurl.com/y8bv8tjl). Charcoal kilns are sometimes erroneously referred to as “coke ovens,” but the construction techniques and purposes differed.

The following three photos show two charcoal sites that were near Price, Utah. These photos have fine detail seldom seen in photos from the period. The photos below are cropped images and have been adjusted for exposure to enhance visibility of details.

- Spring Glen, 6 kilns, ca. 1890. Titled “Upper kilns, Coke Oven, Sunnyside [Utah].” These are not coke ovens, rather they are charcoal kilns. Notice wood being loaded into rear of kiln 1, wood stacks in front, and vents around the base; all features associated with charcoal kilns, and not coke ovens. On close scrutiny, one can see wood protruding from the open door of kiln 2. Doors and vents are sealed for use on the remainder. As there is no historical record of commercial charcoal ever being produced at Sunnyside, the site is more likely J.T. Rowley’s second set of kilns on the north side of Spring Glen. The original scan may be viewed at http://tinyurl.com/ybbuxfq2.

- Blue Cut, 5 kilns, ca. 1889. Although titled “Coke ovens in mining camps,” these were undoubtedly charcoal kilns as evidenced by wood stacked in kiln #1 and on the hill behind it. The doors and vents are sealed on kilns 2 through 5, and kiln 5 appears to have heat rising from the top. Notice the riparian area in foreground and no railroad, yet. There are only three workers shown, which would have been a normal number of colliers for a single site. Western Mining and Railroad Museum identifies this photo as Blue Cut in Spring Glen. The original scan can be found at http://tinyurl.com/ybf5t73p.

- Blue Cut, 6 kilns, ca. 1891. Titled “John T. Rowley.” Rowley was listed in news of the time as the “builder” of both sets of kilns in Spring Glen (Blue Cut and Spring Glen). The picture may depict Rowley and family and what was by then a family operated charcoal operation. A 6th kiln and railroad tracks have been added to the site since the first photo. The original scan may be viewed at http://tinyurl.com/ybk2mr3a.

Hillyard, Wyoming

George Beard (1855-1944) was an LDS merchant, painter, photographer, and Coalville, Utah, resident. A larger version of this image can be found in BYU’s L. Tom Perry Special Collections: http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/

George Beard (1855-1944) was an LDS merchant, painter, photographer, and Coalville, Utah, resident. A larger version of this image can be found in BYU’s L. Tom Perry Special Collections: http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/GeorgeBeard/id/825/rec/5. BYU describes the photo as “Cone shaped small buildings in a field.” The annotator must not have known that these structures were charcoal kilns. Beard’s photo was taken between 1930 and 1939, years after the last use of the kilns to produce charcoal, and the kilns had clearly been converted to storage and/or livestock pens. Remnants of these kilns still remain on the site, which is still being used for farm/ranch storage. The site is on private land, but can been seen from County Road 173 one tenth of a mile to the east.