By Susan Grayzel, Ph.D. and Molly Boeka Cannon, Ph.D.

You decide to tackle that long-postponed task—going through the boxes of material moved from your grandparents’ home into your basement. When you unpack them, you find a box within a box. It might contain some black and white photographs: someone in a nurse’s uniform, someone carrying a flag. It might hold a set of medals, an old cap, a pair of worn-in boots, or a government issued recipe booklet on how forgoing sugar will help win the war, with handwritten annotations next to the family favorites. When looking through these items, you might remember as a child playing with the medals or watching a face light up when looking at a photograph. While many of us have no direct experience with military combat, we often live with the souvenirs, objects, and other remnants passed down from those who did.

Sometimes, the objects collected or saved by our relatives, friends, and neighbors who have participated in the wars of the last century linger on as memorials. These tell us much about how members of our families and communities contributed to wartime activities, overseas and at home. But sometimes, unless we take a moment to ask about the meaning of the stuff in those boxes, we lose their significance and thus a way to understand our shared past.

As co-directors (working with many valuable community partners, as well as students from USU and other volunteers), we are embarking on a community, veteran, and military-family centered project to help preserve the tangible objects that go to and come home from war. Through the National Endowment for the Humanities-sponsored “Bringing War Home” project, we want participants to gain a deeper understanding of the material world of modern war and how that world has been incorporated into our families and communities and revealed in our efforts to memorialize and commemorate these conflicts. In order to do this, we invite the public to share their wartime artifacts and the stories that accompany. In this way, the objects and their stories are able to be preserved and shared with future generations—especially students and teachers.

Beginning this spring, we are hosting several “Bringing War Home” roadshows. These provide an opportunity for the public to take that box and allow our students and volunteers to document and digitally preserve the objects in it and the stories they tell. Our ultimate goal is to create a living digital archive filled with stories and digital representations of artifacts from those in Utah who lived through the wars of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This archive will help us gain a greater appreciation for what objects can tell us about modern war.

Although the history of war, especially of military technological development, is filled with objects, it is only recently that historians have taken material culture during war seriously. As Karen Harvey remarks in her introduction to a guide for history students wishing to use material sources, “as a staple of historical training, material culture has generally been absent from most university history programmes.” [1] Yet, increasingly, historians have learned to see that the materiality of the past offers a rich source base to understand individuals and communities.[2] Scholars of war have recently joined these new attempts to reflect upon the past via an analysis of objects. In a recent collection, Objects of War, the editors Leora Auslander and Tara Zahra urge historians to consider that “people in desperate circumstances [war and its aftermath] rely on familiar things in their efforts to retain memories and maintain a sense of self.”[3] As scholars of conflict archeology have also shown, war is saturated with objects shaped and carried from battlefields to homes.[4] Sometimes such objects end up in museums, but the personal stories of how such objects came to make journeys from Vietnam to rural Utah, for example, often do not.

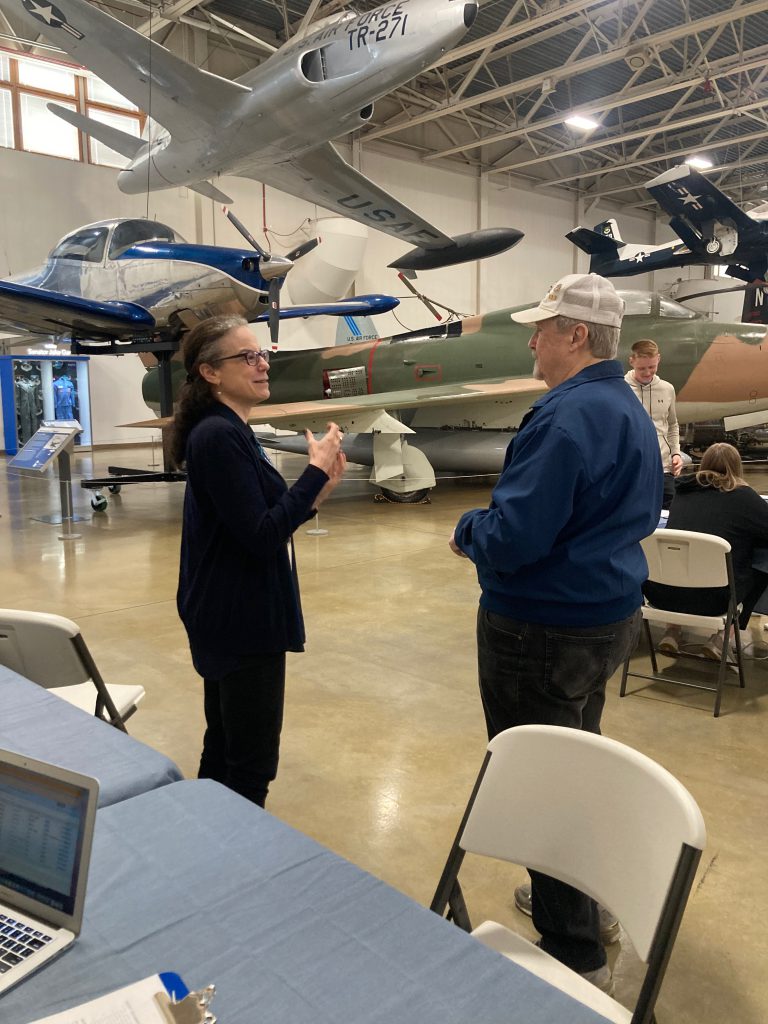

The “Bringing War Home” Project has already begun to digitally collect objects and stories in Cache Valley and at the Hill Aerospace Museum. We look forward to meeting you on the road to learn more about your objects, the stories that accompany them, and our shared history.

Susan R. Grayzel, Ph.D., is a professor of History at Utah State University, whose work focuses on modern European history, gender and women’s history, and the history of total war. She has published extensively on these topics including her recent research on material culture and modern war that appears in her forthcoming book The Age of the Gas Mask: How British Civilians faced the Terrors of Total War with Cambridge University Press.

Molly Boeka Cannon, Ph.D., serves as director for the Utah State University Museum of Anthropology and the Mountain West Center for Regional Studies. Her research and teaching involve understanding life in the Mountain West, she approaches this work through ethnography, archaeology, museum studies, and community engagement.

[1] Karen Harvey, “Introduction: Practical Matters,” in History and Material Culture: A Student’s Guide to Approaching Alternative Sources, ed. Karen Harvey (London: Routledge, 2009), 1.

[2] P. W. Wilderson, “Archaeology and the American Historian: An Interdisciplinary Challenge,” American Quarterly 27 (1987): 115–32.

[3] Leora Auslander and Tara Zahra, “Introduction: The Things They Carried: War, Mobility, and Material Cultures,” in Objects of War: The Material Culture of Conflict and Displacement (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 3.

[4] Douglas D. Scott and Andrew P. McFeaters, “The Archaeology of Historic Battlefields: A History and Theoretical Development in Conflict Archaeology,” Journal of Archaeological Research 19, no. 1 (2011): 103–32; Gabriel Moshenska, “Contested Pasts and Community Archaeologies: Public Engagement in the Archaeology of Modern Conflict,” in Europe’s Deadly Century: Perspectives on 20th Century Conflict Heritage, ed. Neil Forbes, Robin Page, and Guillermo Perez (English Heritage, 2009): 73–79; John Schofield, Aftermath: Readings in the Archaeology of Recent Conflict (Springer Science & Business Media, 2009).