By Steve Cornell, Historical Architect, Division of State History

Let’s look at Lehi. I happen to reside here so I’m looking closely, perhaps a little too closely.

Lehi was an outlying farming community and a small downtown grew out of that, mostly of one-story brick structures. The economy was good with a sugar-beet factory and a roller mill. Lehi stayed small for most of its life. It was a bit of a hick town, and was the perfect urban actor for Footloose, a town behind the times and a tad bit prudish. That’s all changed now. Lehi, with its overabundance of farmland, is now home turf to Utah’s booming tech industry with heavy hitters like Adobe, IM Flash, Vivint and others. With that new found industry and all that empty farmland, Lehi has undergone a population boom that is rarely matched in the State.

The population was 47,407 at the 2010 census, up from 19,028 in 2000. A more recent 2017 estimate reports a population of 62,712. According to the US Census Bureau Lehi was the 11th fastest-growing large city in the nation between 2015 and 2016. Future projections by the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget indicate a continuing trend with Lehi looking at 82,589 residents by 2030. Regional population trends are similarly upward. To the west, both Saratoga Springs and Eagle Mountain City, both of which have considerable association with Lehi, the numbers are even more pronounced. Currently, those areas have a population of about 30,000 residents each, give or take, and the projections for 2030 show an aggressively increasing trend, with Saratoga Springs around 58,000 and Eagle Mountain at 54,000. The other adjacent communities, Highland and American Fork, show 2030 population estimates of 21,000 and 40,000 respectively, a more moderate pace to be sure.

All of these variables factor into Lehi’s future and the regional population of these five communities will reach a near staggering 255,000 residents by 2030. That means there is an enormous pressure on Lehi’s antiquated Main Street, which is a sliver’s width when compared to the more robust examples abounding in Salt Lake.

Because there was so much vehicular pressure on Lehi’s Main Street due to growth in Saratoga Springs, there was serious consideration by the city to pick-up the buildings on the north side of the street and shift them, widening the street to accommodate increased traffic flows. The city began buying up properties in 2008 to plan for such a contingency. The mayor at the time was open to the possibility that Main Street become and expressway to accommodate increased traffic loads.

That proposal was short-lived when UDOT ended up building Pioneer Crossing, but that alternative did not immunize Lehi’s Main Street from the impacts. Even still, Main Street traffic was reduced from 30,000 cars a day to 18,000. In 2009, the old Cotter’s Grocery building’s roof collapsed, and in an effort to mitigate the “fragile dominoes poised and ready to topple,” Lehi City authorized the demolition of it and two other historic buildings, Price’s market and the Lehi Hospital (on State Street), all of which Lehi City owned.

Lehi seems eager to rid itself of its “fragile dominoes” along Main Street. After Porter’s Place closed and relocated to Eureka, the city-owned building sat vacant for a year until it was demolished just in the last couple of months to make way for new development. The city deemed the building unsalvageable and too costly to repair.

As of 1998 when the “Lehi Main Street Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, there were twenty-one buildings that still maintained historic integrity. Two historic buildings had lost their integrity and were seven buildings were built too recently to be included. As a side note, the district did not include the south side Main Street between Center Street and 100 West. Currently, of the original twenty-one, nineteen remain, although some of these have since lost their integrity.

New development filling in the “missing teeth” needs to be closely considered. Is it better than what was there? In the place of “Porter’s,” a three-story medium density mixed-use building will be constructed that wraps the corner and marches up Center Street. It will be the tallest building on Main Street. Although the preliminary design attempts to “break up” the long façade, it will dwarf the adjacent buildings, not only in height but also in its massing. In an effort to fit it in to what residents refer to as the “quaint character of Main Street,” it has been adorned with faux “historic” accouterments. This does not, however, adequately hide its massive scale.

The quaintness that is so desired is being pushed out by the unprecedented larger scale building. The scale and texture of a main street has always been successful because of what is referred to as “Older, Smaller, Better” buildings. “Older, Smaller, Better” was a phrase coined by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The resulting report, produced in 2014, demonstrated quantitative measures of how the “Older, Smaller, Better” buildings and blocks of our towns influence urban vitality. In brief, the report found that areas with “Older, Smaller” buildings are more walkable, attract younger people, are more affordable and flexible for entrepreneurs, appeal to the creative economy, and bolster the local economy as well as supporting a more diverse demographic.

In another “missing tooth,” the city endeavored to create urban open space, with an infill “pocket park” nudged into one of these tight spaces between two historic buildings. It has some landscaping and a bench, but it’s unlikely anyone has lingered here other than to pass through to the parking on the north. Its function is dubious as the block only has a 400-foot street face and is only one of two downtown blocks that make up the main street commercial core.

Further down the street, a 65-foot wide single-story building was built in the recent past and its presence is more dominating than any of the other buildings along this two-block stretch. The façade is adorned with faux-historic details that do little to mask its robustness. The project includes an alley-pass through to the north parking area, again to offer some reprieve from having to march an extra minute or so around the block (the building is only 35 feet away from the end of the block).

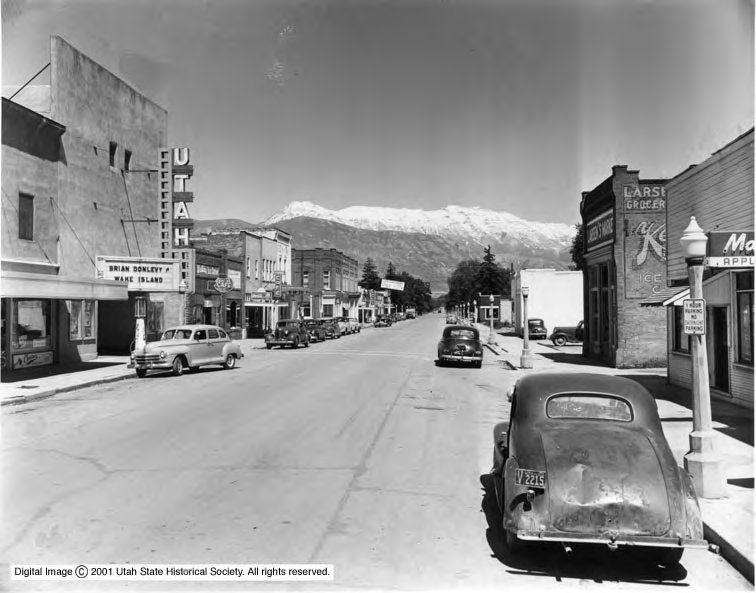

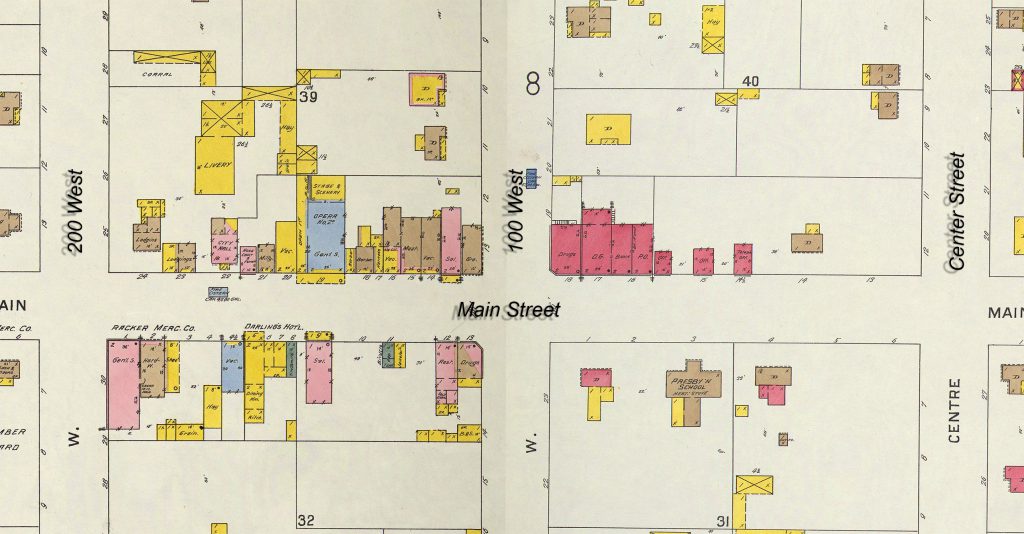

Looking back to Lehi’s early days, a map produced in 1907 shows Main Street not yet fully developed. The block between 200 West and 100 West was largely filled-in but there were still numerous empty lots between 100 West and Center Street. By the late 1930s, however, it had matured into a diverse collection of smaller scale commercial buildings. By that time there were approximately 50 different buildings on Main Street between the 200 West block and Center Street. Today there are roughly 25.

Another way to look at this it to consider the square footage of building versus the square footage of surface parking, and currently 27% of the land is used for building and 34% is dedicated to surface parking. There were relatively few changes up through the 1980s, but some larger buildings were built though in the ‘60s and ‘70s that replaced older historic buildings and better accommodated car traffic.

With all that open space, it indeed seems to be a peculiar proposition to tear down an existing historic building such as Porter’s Place only to replace it with a large-scale structure which will require additional parking beyond what is currently available and further tip the scales toward more surface parking.

Returning to the “Older Smaller Better” study, the key takeaway is to offer support of “neighborhood evolution, not revolution.” Lehi is not by any means a lost cause, quite the opposite. In some cases, it’s easier to tear down than to reuse, and this is largely due to self-imposed hurdles cities have given themselves. At the city level, updating zoning codes, easing parking requirements, and streamlining building permitting are all useful tools to promote reuse, but there also needs to be financial incentives in place to assist these smaller scale projects. In some cases, cities have set aside façade improvement funds in downtown areas to promote reusing existing buildings.

The State of Utah offers cities and counties additional incentives through the SHPO office. Certified Local Governments (CLG’s), meaning cities and counties that have met certain minimal qualifications, are eligible for a matching grant. The CLG must provide a 50% match of up to $10,000. In total, the funds equal $20,000 which is a healthy incentive to owners of historic buildings, especially in our smaller rural towns, to reuse and refurbish and ultimately to revitalize our downtowns.

Though the funds are doled out in small amounts, there are numerous examples of our Utah cities which have taken advantage of these funds year after year, and over time the funds have effected large changes to the downtown cores. One example worth mentioning is the town of Helper. Helper has consistently taken advantage of this grant program and has funded projects year after year for the last 20 years. Helper City is undergoing a renaissance of sorts as an urban arts hub.

After struggling for many years as industry shifted away from coal and railroads, Helper has found a new economy in arts and recreation. Many of the vacant storefronts have been renovated, and there is a vibrant community consisting of art galleries, coffee shops, museums, restaurants, bakeries, tattoo parlors, movie theaters, bars, antique stores, and yoga studios. These are local businesses that give back to the local economy. It’s exactly what a main street is supposed to be.

Furthermore, the SHPO manages the Federal and State Historic Tax Incentive Program. The Tax Credit program offers both a 20% Federal income tax credit and a 20% State tax credit (not just a deduction) to owners who rehabilitate qualified buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In some cases, projects qualify for both credits. Since the inception of the Federal Investment Tax Credit in 1976 over $84 billion dollars have been generated in economic development.

In Utah between 1990 and 2012, $300 million in private capital was invested in historic buildings using one of these programs. The tax dollars returned to Utahn’s pockets and not paid in taxes are a direct reinvestment in Utah’s economy. On top of this, there were a total of 4,969 direct and indirect Utah jobs created using the tax credits between 1990 and 2012.

Whether large or small, historic rehabilitation projects have a net positive impact for the local economy. The former Continental Bank Building in Salt Lake City was vacant and facing demolition. Instead, by taking advantage of historic tax credits, the building was renovated for $22 million (which equated to a $4.4 million federal tax credit in 1997). Local jobs were created out of necessity to support the new business and travelers, whether out of town or out of state, pay not only to stay at the hotel, but indirectly spend money at local establishments. In addition, business taxes are paid locally through lodging, restaurant and sales tax, as well as property tax, that generates local revenue for Salt Lake City.

In Gunnison, the Casino Star Theater sat vacant for years in a run-down condition but was purchased in 2004 by a local foundation and rehabilitated year by year through CLG grants. Over time the project has become a centerpiece of downtown and has catalyzed other business downtown. Between 2003 and 2010, “gross sales in restaurants, apparel, and accessories, and general retail stores increased by nearly 25% even as per capita income in Gunnison was declining.”

Along with local property owners and local investment, these programs support and promote “neighborhood evolution,” a positive steady progression of the downtown, a continued and renewed vibrancy, rather than the cyclical failure and decay of the downtown due to prolonged neglect.