Editors’ note: This is the first of a series of short essays designed to understand historical markers, monuments, and place names in historical and contemporary perspective.

By John Flynn

Place names are important. They can tell us more than the name of a specific spot on the map. They are used to guide us through the world by labeling specific markers for travelers. But place names signify the spiritual or cultural importance of a place, and often indicate the presence of a people. Just as people have done for generations, the Indigenous peoples of Utah have assigned place names to geographical landmarks and features as a means of marking their presence throughout Utah and the Intermountain West. In many cases these names remained for centuries until Euro American place names, superimposed on the landscape, replaced and obscured them.

Place names in the United States are officially kept by the US Board on Geographic Names, which was first created in 1890 to address conflicting names and spellings that faced mapmakers in the American West. The place names that appeared on the first maps of the West derived from Euro American explorers, surveyors, and settlers. As explorers came through, geographic features then carried their names. Most Utahns probably know Lake Powell, named for the famed explorer John Wesley Powell, but it is doubtful that many would know the native name for Glen Canyon or the tribes present in that area. These new place names, authorized and sustained by the US Geological Survey, erase the presence of Utah’s original inhabitants while implementing and elevating the culture and presence of white settlers. The adoption and recognition of Euro American place names tell a one-sided story of Utah’s history.

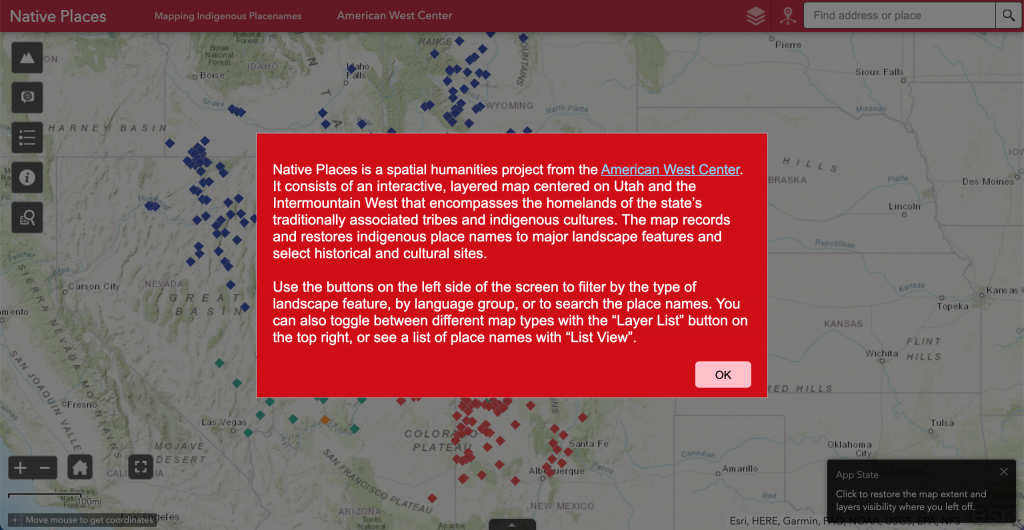

Native Places: An Indigenous Atlas of Utah and the Intermountain West is a geohumanities project aimed at restoring indigenous place names to the features of Utah and the Intermountain West. As a geospatial humanities project from the American West Center at the University of Utah, Native Places uses GIS, digital media, historical research, and tribal consultation to create an interactive map that prioritizes the indigenous names of geographic features and cultural sites that settler-colonialism has erased. By using publicly available data from the USGS, Native Places works against a colonial framework to create a decolonized map of place names in the Intermountain West. While certain contemporary political boundaries are present to help orient users, the map extends beyond state boundaries, since Native homelands traditionally expanded into the modern states of Montana, Idaho, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico. Unlike drawings of territorial tribal boundaries, which are static and limiting due to the changing nature of these lines throughout history, Native Places allows viewers to see the spread of Native homelands through their linguistic presence. Since each place name is based on USGS coordinates, the map also maintains a precision that territorial boundaries cannot. Moreover, since many features have a name from various groups, the overlap of place names tells a nuanced story of territory and presence.

Native Places aims to serve as a tool for cultural heritage preservation and language learning. But the map can also help to reshape contemporary understandings of the land of the Intermountain West. Not only does the restoration of native place names serve as evidence for the history and presence of Native peoples. Moreover, because the map uses linguistic data points rather than the arbitrary shapes created by state, territory, and tribal boundaries, we can learn a more nuanced and complex Native history. Several features have names from different groups, and the colored points on the map overlap, revealing that Native groups moved around and inhabited large areas and interacted with surrounding neighbors. When specific features hold various names and translations, the importance of that feature to Native groups cannot be ignored, and the presence of USGS names displays how settler-colonialism can erase culture.

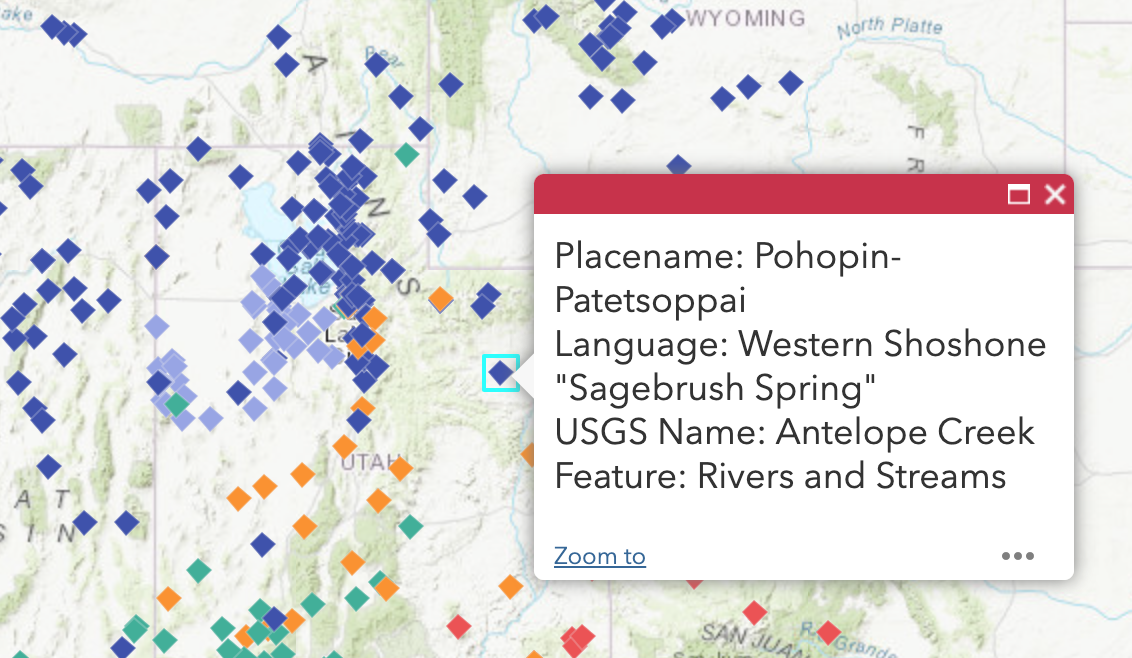

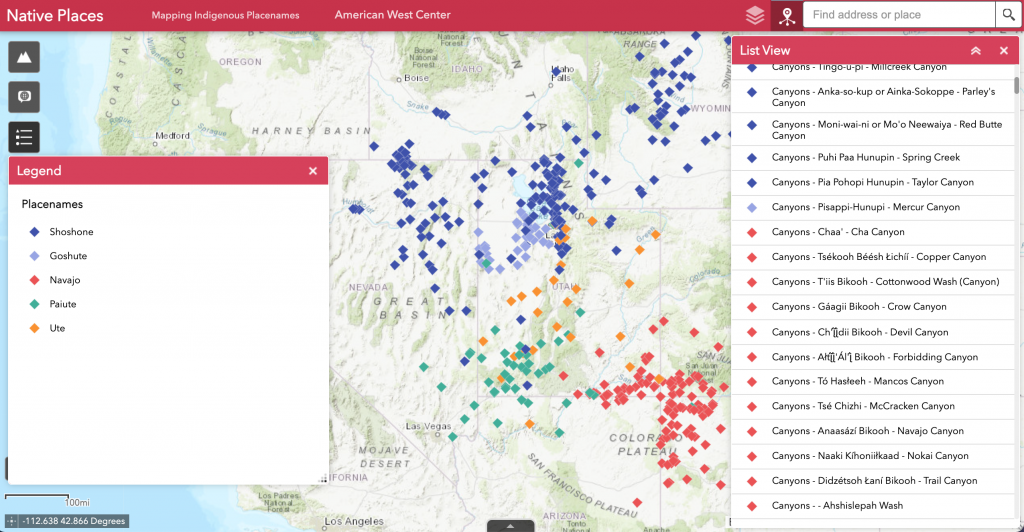

Users of the interactive map will be able to explore the Intermountain West through the Native languages of the tribes of Utah. While the state of Utah recognizes eight tribes—Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation (Shoshone), Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation (Goshute), Skull Valley Band of Goshutes (Goshute), Ute Indian Tribe of Utah (Ute), White Mesa Community (Ute), Paiute Tribe of Utah (Paiute), San Juan Southern Paiutes (Paiute), and Navajo Nation (Navajo)—the map is divided into five cultural groups in order to provide clarity. Five color categories represent these five cultural groups, the Ute, Shoshone, Goshute, Paiute, and Navajo. Points on the map will also contain a popup with more textual information, including the dialect, the native place name and its English translation, the official USGS name, and the feature type. Currently, Native Places contains nearly five hundred points that represent indigenous names for features such as rivers, mountains, canyons, and cultural sites. The map has several interactive features that will allow users to toggle between the language groups and geographic features and search for specific points by either the indigenous name or the official USGS name.

The map itself uses a topographic base that illustrates the geographical features of the Intermountain West. Certain modern political boundaries and cities are present to orient users, but the spread of colorful data points move well beyond the arbitrary rigidity of state lines. Users may explore place names by clicking on the various markers, or opt to filter through points based on categories. Two tools on the side of the map allow users to view any combination of language groups or geographic features. For instance, one may opt to view only mountain ranges and peaks that have a Navajo or Ute place name.

While the goal of Native Places is to serve as an educational and linguistic preservation tool, respect for tribal traditional knowledge is a key concern. Out of respect for tribal knowledge and to safeguard against non-Native trespass, the map will not name or show the location of sacred sites. The data is also stored on Mukurtu, an open-source management platform built with Indigenous communities and designed to manage, protect, and share digital representations of cultural knowledge. Mukurtu allows prioritized levels of access depending on group affiliation. This means that tribes can maintain ownership over cultural heritage, deciding how and with whom information is shared.

Native Places is inherently a collaborative effort meant to benefit both the tribes of Utah in cultural preservation and the general public in education. Cooperation between the American West Center, the Digital Matters Lab at the Marriott Library, and tribal leadership is integral to creating a successful vision of this project. The map is editable and adaptable, so as Utah tribes submit place names, or new research is conducted, the breadth of the map will grow. The hope of Native Places is to provide tribes with a tool to teach and maintain their Indigenous languages and to educate Utahns on Native history through the presence of place names in the Intermountain West.